Search the Site

Guest Blog post # 100: "When 'Alt' IS Right" by Bill Woods

Recently on one of those community Facebook pages someone posed the question “What’s the most important quality to establish in your horse?” If you discount the glib, knee-jerk clichéd replies, it’s a question that defies a single answer given the huge variation from one horse to the next and how differently one trainer approaches his work from another. Rather than settle on an agreed conclusion, the query was more raised to provoke discussion.

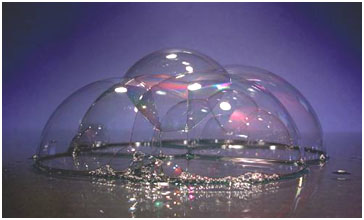

In DRESSAGE Unscrambled I suggested that the training scale or training pyramid is often misconstrued by well intentioned neophytes. I prefer to think of it as a training soap bubble. This is because the qualities which we seek to develop are so intertwined and codependent that it is unrealistic to view them as a linear progression. While rhythm and relaxation are the foundation level of the pyramid, depending on the horse’s issues it may be necessary to “jump ahead” and try to make him straighter or more flexed (or whatever) before that primary goal can be achieved.

Establishing relaxation, we know, is vital but it doesn’t mean waiting endlessly for a passive, noninvolved mindset to develop in your horse … at which point he is no closer to being trainable and may even be more perturbed if his new normal is suddenly disrupted.

If you are successfully working your way up through the levels of dressage on an appropriate horse, what I’m about to say will seem very foreign, but not every rider is as fortunate as you. Highest on my list of desirable rider skills is Survival. That may seem laughably obvious, but more than once I have heard a rider who had just (barely) escaped a very dangerous situation explain, “Well, at least I didn’t pull on the inside rein!” This is akin to remembering to fold your napkin after your ship hit the iceberg. Nice, but it won’t reserve you a place in heaven. There are simply times that Undressage trumps any classical artifice you have been taught. I met one woman in a clinic whose slavish devotion to a 20 m circle only produced an egg which bulged towards the gate every time she passed it. Short term solution – abandon the circle. For that matter abandon the arena. Forget about being on the bit. Practice making the horse go straight, remaining in the corridor between her two legs no matter where she pointed him anywhere in her workspace. First things first!

Or as I said earlier, sometimes second things first. Charles deKunffy once told me, it is a trainer’s responsibility to enhance the gaits of the horse. That’s a long-term strategic goal. However, there may be moments where a short-term sacrifice of the movement is necessary to create the right working relationship.

So again at a clinic along came a big coming-four year old stallion ridden for his owner by a talented and athletic young man. In this new environment the horse was acting out in extreme ways. Watching them, as he spun and leapt I doubted I could have stayed on top of him. Or at my age had wanted to try. Eventually he settled and moved in an adequate but totally uninspired manner. He was round. He tracked up. The way he went was probably worth a Training Level seven. But he was hardly a picture of what I wished I could take home with me despite his billing as a fancy young stallion I was supposed to slather over. He was not greatly stressed – not really intimidated— but he had politely retreated into his shell and obediently offered only the most mundane way of going. By the clinic’s third day his erratic behaviors had totally disappeared but he just looked unspecial. Now it was time to grant him freedom. This was not freedom to make things up on his own but rather offering him space within the aids to flow forward and get loose. Initially in this phase we made no attempt to shape his top line — simply rode him forward into space or at best a passive contact and a stabilized tempo. Because at this point he was not inclined to run off, we made many lengthenings, inviting him to step way up under himself and to feel free to throw his shoulders. And as the quality of his movement reemerged, the next step was to surround him with the aids again.

Putting this young horse as together as much as his rider had is not necessarily in your standard playbook. It was a necessity born of the stallion’s assertive personality. Later asking him to work on a long or loose rein and rediscover his exotic movement isn’t either, but by then his reactions and expectations had changed. He had earned the right to express himself and had bought into the “trained” context in which to do it.

On reading all this I don’t want you to conclude I am just preaching Undressage. However, I remind you of that line “To a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.” Switching images, a good doctor will often tell you her (or his) most important skill is making an accurate diagnosis of the patient’s problem. From this (with appropriate creativity when required) they can solve the problem. And so can you.